Legalizing Responsibility for Human Rights in Global Supply Chains

June 2, 2016

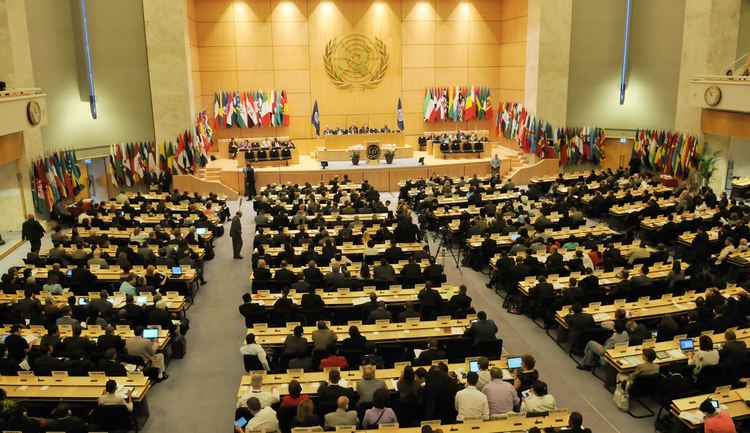

In the lead up to the annual June 2016 conference of the International Labor Organization (ILO) there has been a flurry of reports and public statements from NGOs and unions on one side and from industry on the other which reflect the polarized nature of the debate about global supply chains. On the one side NGOs and unions are calling for new regulations governing these global supply chains. Human Rights Watch launched its report on ’Human Rights in Supply Chains’ and called for “a new, international legally binding standard that obliges governments to require businesses to conduct human rights due diligence across the entirety of their global supply chains.” The International Corporate Accountability Roundtable (ICAR), in an open letter to the ILO also appealed for a new international standard on human rights due diligence and highlighted the need to ensure transparency in global supply chains. In a report documenting the poor working conditions in global garment production, the Asia Floor Wage Alliance requested the ILO urgently “move towards a binding legal convention regulating GVCs (global value chains)”.

By contrast the opening statement by Employers to the ILO meeting emphasizes that there is “broad consensus in the business community” in support of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Their statement stresses Principle One of the UNGPs which says that states have the primary duty to protect human rights. Accordingly they conclude “it is the Employers firm position that no new standard-setting on supply chains is required.” The gap between these two perspectives is significant.

While there is no doubt that global supply chains have long been associated with a range of human rights violations, such harms are now being increasingly well documented, leading to greater demands for corporate accountability. The Associated Press won this year’s Pulitzer Prize Public Service Award for its in-depth investigation into forced labor practices in the Southeast Asia seafood and fishing industry. NGOs have been recently highlighting the appalling living and working conditions of migrant workers in Gulf countries as they work to build stadiums and museums in Qatar and the UAE. The collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh in 2013 placed a spotlight on the poor conditions in Bangladesh’s garment factories where many workers continue to work long hours in unsafe conditions.

The challenges of regulating global supply chains are inherently linked to the broader challenges of regulating business in a globalized world. Many companies operating in multiple countries utilize vast global supply chains to bring their product to market. These supply chains often rely heavily on sub-contracting, or ‘indirect sourcing’. That is, a company will have a number of suppliers with whom it contracts directly (also referred to as ‘first-tier’ suppliers) and these suppliers will then sub-contract out some (or all) of the work to further suppliers down the chain. The depth and complexity of such supply chains operating in the shadows of Bangladesh’s garment industry was recently examined in two reports from NYU’s Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. These complex and indirect relationships pose significant challenges, particularly when considering regulation and international law responses.

Government reporting requirements are a first step in linking transparency with accountability. Recent legislative advances asking companies to report on specific issues in their supply chains, such as the UK’s Modern Slavery Act, California’s Transparency in Supply Chains Act or s.1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Act, do not guarantee accountability. Rather they aim to utilize corporate reporting as a tool that has the power to advance accountability by increasing transparency around corporate operations which may then trigger pressure to improve corporate human rights performance.

Ultimately, laws – whether national or international – are only as strong as their enforcement capacity. While these American and British legislative developments mandate disclosure, they do not directly impose civil or criminal liability on lead firms for the downstream acts of other companies in their supply chain. However, transparency legislation can also be crafted to expressly attach legal liability up and down a supply chain for particular wrongdoings occurring anywhere in that chain. This type of legislation emphasizes the link between leverage and responsibility. If a firm at the top end of the supply chain can control the size, design, quantity, and quality of a product, and possess potential leverage to influence the working conditions of those producing the goods, it is then both fair and effective to align that power with legal accountability. Chain liability, as used selectively in Australia’s homeworker industry or the EU’s construction sector, can shift the overarching legal responsibility to the firms at top of the supply chain making them liable for harms occurring in their supply chain. If companies can demonstrate that they have exercised due diligence in such circumstance, this could be a defence to liability. Regulations that incorporate penalties – for failing to report or conducting inadequate due diligence – are more likely to be an effective deterrent than those that do not.

Laws imposing legal accountability in supply chains challenge the traditional corporate law framework which promotes limited liability and the separate entity doctrine. In essence, what such laws are attempting to do is bring a broader and arguably more modern sensibility to determining which firms in a supply chain might be traditionally understood as falling within a corporate group. On a parallel track over the last four decades a number of governments have adopted laws and regulations aimed at holding companies accountability as part of their broader efforts to combat global corruption. Global supply chains are an intrinsic part of most modern corporate operations. This is reflected not only by the approach of global companies in how they structure their operations, but also emerging soft and hard laws aimed at reducing negative human rights impacts in supply chains. Due diligence and reporting provisions can be a useful tool to utilize the leverage of lead firms to improve supply chain working conditions but such laws should be crafted in a way that utilizes the leverage of these global companies to improve working conditions and penalizes them if they do not. An approach focused on blending (and protecting) private interests and public intervention seems to offer a viable way forward.

Global Labor

Global Labor