ABA Backs Human Rights Mediation for Development Projects

February 18, 2025

A new resolution by the American Bar Association promotes engaging with indigenous communities and other vulnerable stakeholders at every step of a development project. In an interview with the NYU Stern Center, the architects of the idea explain how it would work.

On Feb. 3, the American Bar Association passed Resolution 607, to “encourage parties to international development project agreements to provide in such agreements for the establishment of ‘conflict management committees’ to anticipate, prevent, de-escalate, resolve, and remediate conflicts and harms among stakeholders before and during project development.”

Sounds intriguing – but what exactly is a “conflict management committee”? The innovative concept has been incubated by the OHADAC Regional Arbitration Centre – also known as the CARO Centre – with funding from the European Union.

In this Q&A, NYU Stern senior research scholar Michael D. Goldhaber speaks with CARO Centre secretary-general Marie-Camille Pitton, and Elise Groulx Diggs, lead drafter of the CARO conflict management rules that inspired the ABA’s new resolution.

Michael D. Goldhaber: The ABA’s new resolution embraces the idea of heading off disputes by incorporating human rights and environmental mediation into the early stages of a global project. Marie-Camille, you run the CARO Centre. Was there any eureka moment in your work when you realized that dispute boards are not engaging workers and communities enough?

Marie-Camille Pitton: I’m not sure there was a eureka moment – but as I looked at investment arbitration, I realized that it’s imbalanced. Here the investor can use a forum where human rights and environmental issues will never be discussed. This is really problematic, because in local courts these issues are not strictly separated. They’re part of the imperative rules taken into account by the judges, including the commercial judges, reflecting the unity of a legal order that does not yet exist on the international plane, where international law remains fragmented. So, this is what bothered me first in this field. At the same time, I realized that many companies no longer want to fight these expensive claims, and they also have obligations in terms of ESG. So ideally, you don’t want to reach the claim stage, and you want to make sure that from the beginning of the project ESG is taken into consideration. When we were asked to create a dispute resolution service, I thought: ‘Why not work on these issues in a very concrete way from the start?’ Especially in light of the fact that ESG is now part of these contracts anyway. You don’t even have to rely on public policy; it’s in the contract. So why leave it on the side? I’m hoping that by creating this framework we will get the stakeholders used to implementing ESG as part of normal applicable law. Then, if it does go to arbitration, I hope it will be easier for arbitrators to consider the applicable law as a whole.

MDG: In a way you were addressing a gap in legal infrastructure that’s in no one’s interest. You noticed that arbitrators often ignore the workers and the community. Yet when companies ignore the workers and the community, they can lose their social license to operate. Elise, how did you become involved?

Elise Groulx Diggs: A few years ago, the commercial mediators Mark Appel and Wolf von Kumberg asked me to join a task force advising the International Chamber of Commerce on mediation prior to investment arbitration. I was excited because I have a background as both a human rights lawyer and a mediator. But I set a precondition. I said I’m interested if we explore the possibility of co-mediation – to have a mediator representing stakeholders who are affected by projects. Then, in the Fall of 2022, Marie-Camille told me her center wanted to hire me to reconsider how a dispute board could engage with stakeholders. I was thrilled. So, I went back and asked Mark and Wolf to help me develop co-mediation for the CARO Centre. They immediately said yes. It’s been a convergence of lawyers with very different backgrounds who came together with a shared vision.

MDG: Elise, you have experience as a mediator in disputes from Canada to Africa. Can you give us some egregious examples of projects that were either killed or terribly delayed because of a failure to engage with stakeholders?

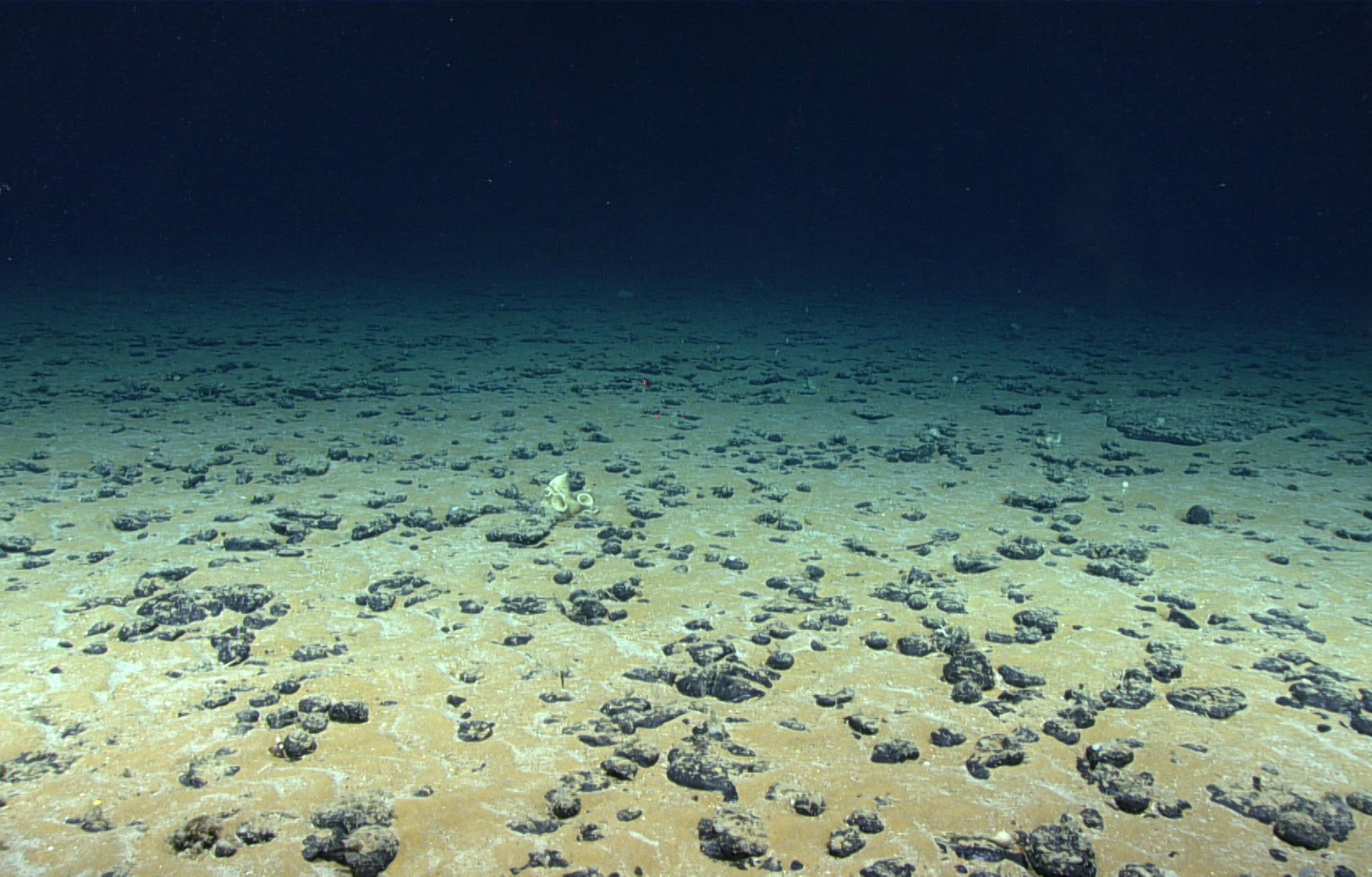

EGD: There’s a very good example in Panama. So, Panama had a conflict with the indigenous people with a big Canadian mining corporation. The Supreme Court reviewed the evidence related to the lack of respect of indigenous people’s rights and the environment. The Supreme Court of Panama [in Dec. 2023] then decided that the contract had to be declared void. They ordered the closure of the mine. That mine was generating over 50,000 jobs in Panama and it was a multibillion-dollar source of revenue for Panama; its operations covering mostly copper, which is very important to the climate transition.

MDG: The next question is nuts and bolts. The two of you have designed a process where managing a potential dispute with stakeholders is baked into a project at every stage. Can you walk us through that process?

MCP: Sure, yes. First the parties need to provide in the contract that there will be a Conflict Management Committee, or CMC. Then the CARO Centre will set up a committee of one to five members. In a traditional committee you will have dispute specialists and an engineer. Here you have also an ESG specialist. Once the committee is in place, there’s an important first meeting with all the stakeholders, where the ESG expert sets up a regular dialogue with the rights holder and the affected communities, and the CMC makes an agenda to monitor the project. Because – if there are difficulties – the aim is to kill them before they become proper claims. Then there’s another crucial step up front, where commitments are made toward the stakeholders. And then the CMC meets every 4 or 5 or 6 weeks until the end, with special channels if there is a need for formal mediation. This is the basic timeline, with some escape routes if needed.

MDG: Who appoints the members of the committee?

EGD: Typically, the contracting parties each propose someone, and the CARO Centre appoints them if it agrees. Then the CARO Centre chooses the expert on ESG matters, and that one becomes the chair.

MDG: Elise, in what sorts of projects do you imagine these rules being most useful?

EGD: We’re usually talking about big infrastructure projects. Whether it’s mining, energy, agribusiness, forest, land, renewables, anywhere in the world.

MDG: What are some of the issues that arise?

EGD: Well, if I take the case of Peru for example, there’s been resistance to mining operations for decades. These sorts of social conflicts never get resolved. They don’t work themselves out. They deteriorate with time and become worse and worse until the communities do not trust anyone anymore.

MCP: But also, traditional construction issues, like the implementation of contracts, critical delays, or the quality of the work. These are intertwined with social and environmental issues, because when a contract is disrespected, it can create unsafe labor conditions, and conversely, pollution can create contract issues. Which is why this adds value for companies. We try to take the full perspective. The idea is to create a dialogue that would not otherwise exist.

MDG: I’d like to talk now about how the CARO rules fit into the larger mosaic of international law. Elise wrote a seminal article about human rights as a galaxy of norms, and Marie-Camille has three advanced degrees. So, you guys can help us understand the sometimes-confusing welter of soft and hard law. For instance, UNCITRAL is drafting guidelines to prevent investor-state disputes. How can the Caro rules help?

MCP: UNCITRAL has set up a working group on reforming investment arbitration. As part of that mandate, they are exploring mechanisms to prevent investment disputes. We were very fortunate to have the representative of Jamaica propose adding a reference to the Caro Centre CMC as an official mechanism of dispute prevention.

MDG: I think their key point was that investor-state disputes flow from environmental or social issues that are ignored by investors.

MCP: That’s true. And the affected communities are punished several times over. When the communities argue for their rights, the state reacts – but that may expose the state in arbitration, and lead to increasing obstacles to indigenous rights being acknowledged.

MDG: There’s also a UN Working Group drafting a treaty on business and human rights. How might the Caro rules come into play there?

EGD: Giving rights holders a proper Access to Remedy is the neglected pillar of Business and Human Rights. I am quasi-obsessed with the need to better address this issue. The beauty of a stakeholder engagement plan is that it allows for agreeing on and planning remediation in advance, before a dispute develops. We’ve been approaching Equator Principles banks and development agencies to explain that if they have this kind of mechanism in place, it helps to protect their investment, it provides some kind of protection for their investment. And the fact that their commercial partners are willing to sit down and create this kind of mechanism shows their good faith. We’re trying to get funders to see how trade is connected to human rights. If you think about a state that’s on its knees for revenue, they’re ready to allow the worst labor conditions to get a company to invest in their country. That’s where a lot of unsafe and unfair work practices start. Inspired by the CMCs, we’re also discussing a model contractual clause to implement some monitoring mechanism in a supply chain – as a part of responsible contracting. So again, each time there’s a conflict in the supply chain it could be resolved on the spot. We’re encouraged to uncover and develop all these possible applications. We’re trying to position stakeholder engagement as a cornerstone of the Just Transition.

MDG: Will the EU’s vast new regime for regulating business and human rights, as it kicks in over time, generate new demand for tools like the Caro rules?

EGD: The due diligence directive in its current form has strong language on stakeholder engagement as a corporate obligation. Hopefully that will also clarify the obligation under French law, where it has been the subject of some debate. As you may know, the European directive establishes a kind of committee of control. We’ll have to see what the powers of that control board include. But it’s certainly compatible in spirit with our conflict management committee. There’s nothing else similar that now exists.

MDG: It’s not only that these rules can avoid disputes. They also can show that a company is fulfilling its duties under the due diligence directive, that they have neutral processes in place to prevent or mitigate rights abuses, and provide access to remedy.

EGD: Exactly, absolutely. And if we can get a model clause to be adopted on both sides of the pond to implement some kind of monitoring entity in the supply chain, that would also play a big role in mitigating harm and unfairness in the supply chain. I hope we get language in bilateral investment treaties from the beginning, so that these BITS stop overlooking these issues. We’re not there yet.

Marie-Camille Pitton holds degrees in international law from Harvard, Oxford, and Universite Paris I. She practiced at the global law firm Orrick and served as counsel at the ICC International Court of Arbitration, before becoming secretary general of the OHADAC Regional Arbitration Centre (also known as the CARO Centre), which offers mediation and arbitration services in the Caribbean region and at the global level. As part of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in the Caribbean (OHADAC) project, the CARO Centre is based in Guadeloupe (French West Indies), and presided over by Sir Dennis Byron, former President of the Caribbean Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. The CARO Centre is co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund under the auspices of the INTERREG CARAÏBES program.

Elise Groulx Diggs is an international barrister and has been named by Chambers and Partners as one of the five most eminent practitioners in the world in Business and Human Rights. She has held leadership positions in the business and human rights committees of both the ABA and the IBA. She is also an international mediator, and served as lead drafter of the CARO Centre rules on conflict management.

Michael D. Goldhaber is a Senior Research Scholar at the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. He previously served as US Correspondent for IBA Global Insight magazine, and Senior International Correspondent for American Lawyer Media.

Values-Based Investing

Values-Based Investing Global Labor

Global Labor Business & Human Rights Leadership

Business & Human Rights Leadership