Align, Yes, But Also Enforce: Germany Must Embrace EU Standards and Enforce Due Diligence

April 11, 2025

Germany’s new government is moving to replace the country’s pioneering corporate human rights law with comparable European standards. This attempt to level the playing field for companies operating in Europe makes sense, but to protect human rights, Germany must preserve and strengthen its ability to enforce the European Union due diligence directive.

On April 9, three German parties announced a deal for the formation of a new government that included elimination of the German Supply Chain Act. This innovative law, known as LkSG, required companies to conduct human rights and environmental diligence in their own operations and in supply chains.

Markus Söder, leader of the conservative CSU party, said at a press conference that “the LkSG is now history.” For the CSU and its sister-party, the CDU, the elimination of the LkSG was a central element for the coalition agreement with the SPD, a center-left party. During the elections, CDU and CSU highlighted the need to promote the competitiveness of German companies by reducing bureaucracy that such laws allegedly engender.

But importantly, the German coalition also committed to replacing the LkSG with comparable European legislation. The EU’s new Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) sets out obligations for companies to assess and remedy harms created by their upstream supply chain and some downstream activities such as recycling and distribution.

Germany’s decision to fully align requirements for companies with European regulation reinforces a level playing field for European companies.

Adopted in May 2024, the CSDDD will not take effect until mid-2028, and the so-called EU Omnibus proposal cuts back on the scope and ambition of the original directive. But despite of these recent modifications, it is now clear that human rights due diligence requirements are here to stay for companies in Europe — and that’s a positive development.

The key to the effective implementation of human rights due diligence is its enforcement through national supervisory agencies. Germany created a well-equipped supervisory body for the LkSG under its Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA).

The BAFA as a supervisory body needs to remain active for two reasons:

- First, although the CSDDD will not take effect until mid-2028, supervisory bodies have an important role to play to prepare companies for the new requirements with guidelines and capacity-building. The CSDDD requires companies to address all human rights abuses in global supply chains that companies can know about. Still, many companies are not able to fully map their supply chains, let alone identify and prioritize risks. Reports from media, civil society and academia point out connections between companies headquartered in Europe and human rights abuses in deeper layers of global supply chains. These publications create a body of “plausible information,” which, according to the EU omnibus proposal, should prompt companies to act. National supervisory bodies can help to collect and curate these publications for companies and pool expertise on how to address these human rights challenges.

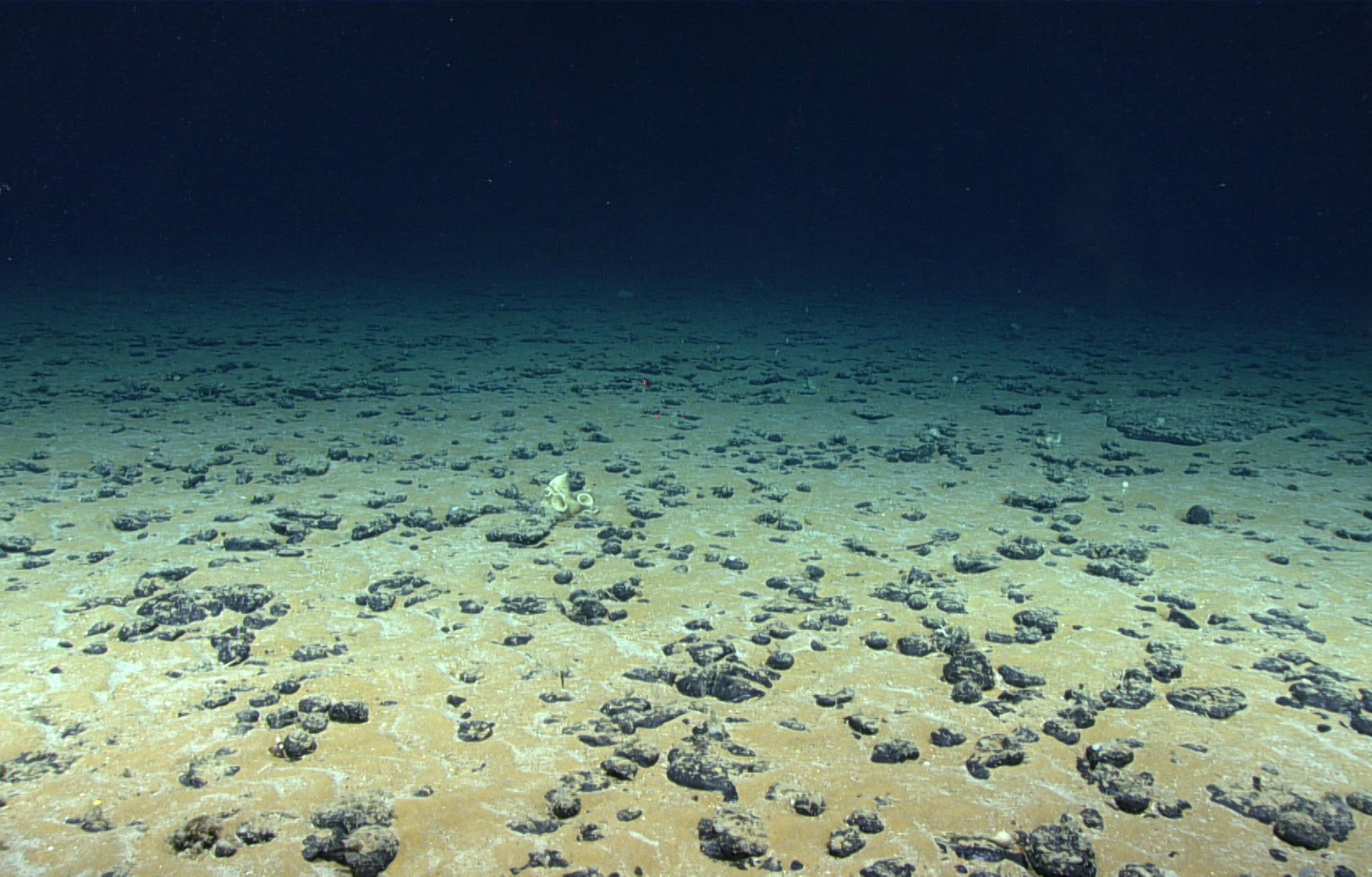

- Second, despite of the pause on all reporting and implementation obligations for companies, there remains according to the coalition agreement the potential for government sanctioning for “cases of serious human rights violations.” To date, no further explanation has been provided regarding which cases would be considered “serious.” But at a minimum, certainly all abuses against core international labor standards as defined by the International Labor Organization need to be assessed by a supervisory body. Concretely, this means that, for example, German car manufacturers still need to establish responsible sourcing strategies for cobalt. The supply chain for this valuable mineral — needed as an ingredient in electrical vehicle batteries — is tainted by mining accidents and child labor in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as documented by human rights NGOs and academia. Similarly, German apparel brands need to continue contributing to compliance with international labor standards in apparel factories in Southeast Asia, where cases of forced overtime or harassment are common.

While the LkSG will disappear, the fundamental concept of human rights due diligence won’t. CSDDD will require a level of human rights due diligence that companies are still learning to address effectively. Supervisory bodies such as the unit in the German BAFA can help companies to get ready. Preserving and promoting enforcement of due diligence laws will benefit workers everywhere. But for workers in global supply chains, where governments are unable or unwilling to protect basic rights of their citizens, enforcement measures in Europe are often workers’ best bet for decent work.