The DRC Is Finally Opening A Legal Path for Informal Cobalt Mining

May 27, 2025

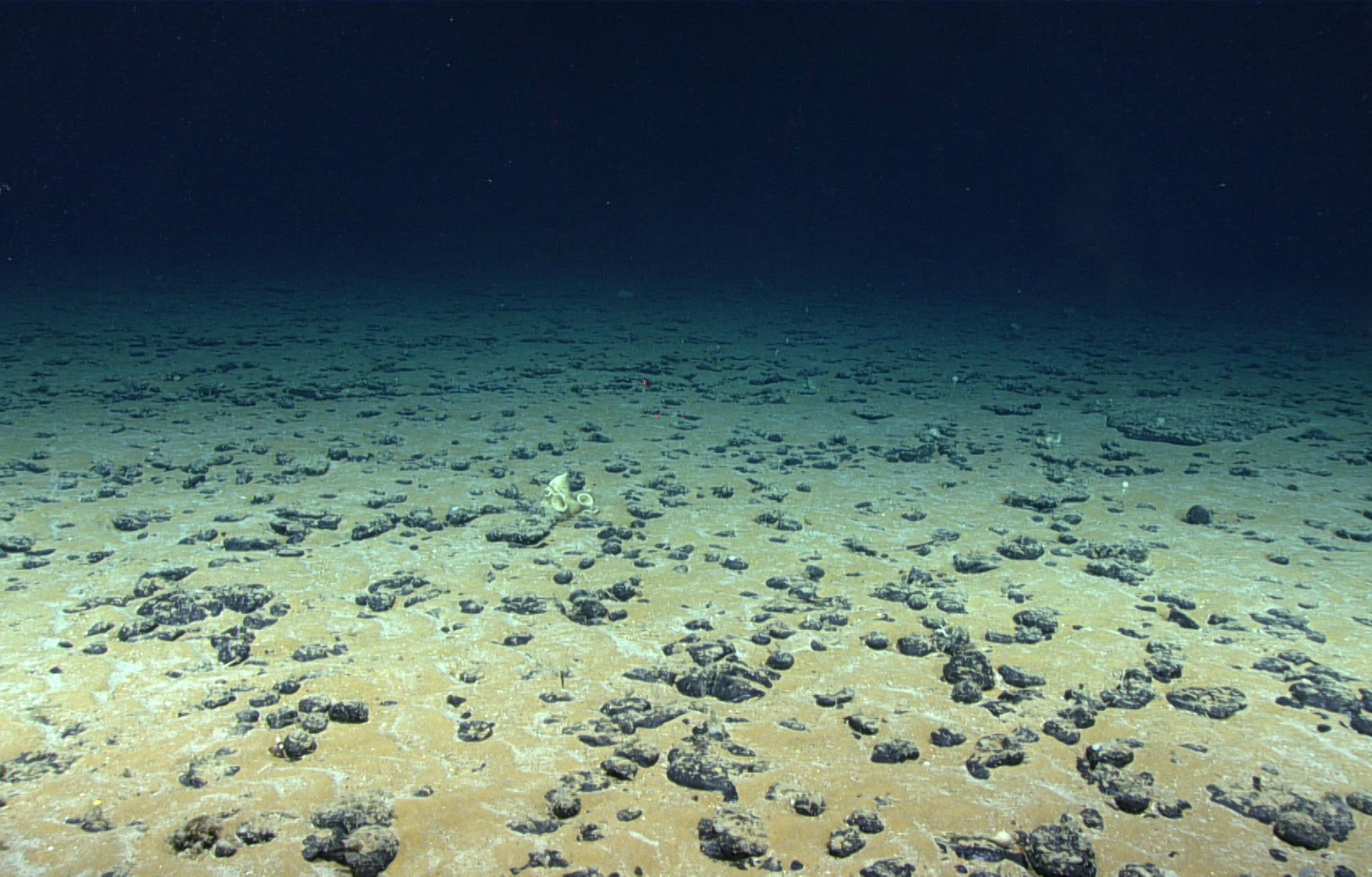

Cobalt is an essential ingredient in batteries for electric vehicles, with natural coolant properties that prevent batteries from catching fire. More than 70% of the world’s cobalt is currently produced in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), about a fifth of which is mined by hand in informal, artisanal small-scale mines (ASM). Hundreds of thousands of workers scramble to make a living in these unregulated and routinely dangerous sites, including an estimated several tens of thousands of children. The minerals they gather are co-mingled with cobalt from mechanized sites, both at these mine sites and later during smelting and refinement processes, mostly in China.

Thus, it is an inconvenient truth than every car company and electronics firm have ASM cobalt in their supply chains. This is a business reality in the DRC, and it means that the big auto manufacturers in particular have a responsibility to help ensure decent working conditions for these artisanal miners by creating formalized artisanal mine sites on industrial mining concessions

Until now one impediment to progress in addressing child labor and mine safety in the ASM sites was what some experts called a “legal grey zone” for the integration of ASM in industrial mining concessions. While The DRC government had created about 40 dedicated zones (Zones d’Exploitation Artisanales, ZEA) for artisanal miners to work, these legally designated zones are often not used by artisanal miners because they have not been systematically tested for cobalt reserves.

Instead, miners typically choose to work on or right next to industrial mining concessions where expensive geological studies had been conducted and where they know cobalt is in the ground. They are understandably hesitant to dig holes by hand in places with unproven reserves. Some of these ZEAs also are far from where miners live and where they can sell the cobalt they collect.

Earlier this year, on February 21, the DRC government finally amended Article 8 of Decree n°19/15 (Modifications of Decree 19/15) which for the first time opens a pathway for mine operators with an industrial mining permit to integrate artisanal miners onto their concession and to create safe workplaces for them. ASM mining has itself never been illegal in the DRC but these miners are required to register their activity with the government and to join a cooperative.

Under this new law, companies that run industrial mine sites will be allowed to assign land to a government owned entity call the Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (EGC), which was created in 2019 to improve the working conditions of artisanal miners. With the modified decree in place, mine-operating companies can work with the EGC to set up formalized ASM sites.

EGC already has published responsible mining standards to address mine-safety issues as well as child labor in these informal sites. These standards were derived from a pilot project, launched by a coalition that included agencies of the national and provincial DRC government; Chemaf, a Dubai-based mining company; Trafigura, a global commodity trading firm that purchases copper and cobalt from Chemaf; COMIAKOL, a Congolese mining cooperative active at the Mutoshi consession; and Pact, a nonprofit that specializes in making ASM safe, formal and more productive. In 2018 they initiated the first ASM formalization project at a mine site called Mutoshi. They took a number of sensible steps to protect workers including the creation of a fenced-off project site with access to open-pit mining, the provision of personal protective safety equipment such as boots and helmets, capacity-building of the cooperative, and the full integration of female miners.

During the pilot phase of ASM formalization at Mutoshi, no fatal accidents were recorded and access for children and pregnant women was prevented with strict entry controls to the project site. Our analysis of the Mutoshi pilot concluded that the formalization process there was both commercially viable and it was effective in addressing key human rights concerns.

Until now the legal grey zone has been a significant barrier to replicating the Mutoshi concept at other industrial mine sites. For example, in conversations I have had with project partners of “Cobalt for Development” in 2020, an initiative run by the German Development Agency (GIZ), they repeatedly cited the legal grey zone as an impediment to their undertaking other ASM formalization projects.

Fortunately, the legal pathway is now open for Cobalt for Development, for mining and trading companies, for large auto manufacturers, and other foreign buyers to finally address the problems of child labor and mine safety issues that have plagued cobalt mining in the DRC for decades. This is the time for them to do so.

Global Labor

Global Labor